Roles, Responsibilities, and Collaborations

An application implements a system of responsibilities. Responsibilities are assigned to roles. Roles collaborate to carry out their responsibilities. A good application is structured to effectively fulfill these responsibilities. We start design by inventing objects, assigning responsibilities to them for knowing information and doing the application's work. Collectively, these objects work together to fulfill the larger responsibilities of the application.

Objects and their responsibilities provide the common core for our new development process, techniques, and tools.

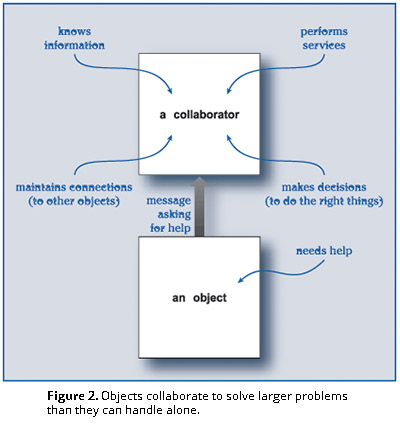

One object calls on, or collaborates with, another because it needs something. Both parties are involved. One needs help; the other provides a service. Objects work in concert to fulfill larger responsibilities. Designing collaborations forces us to consider objects as cooperating partners and not as isolated individuals. Design is an iterative and incremental process of envisioning objects and their responsibilities and inventing flexible collaborations within small neighborhoods.

Clearly defined objects that stick to the point when implementing their roles are easier to understand and maintain.

The services that an object holds and the information that an object provides define how it behaves when it exists alongside other objects. In early design, it is enough to know that particular responsibilities are clustered into objects. First and foremost, an object is responsible for providing and doing for others. A design model arranges responsibilities among objects. We will explore this issue in greater detail later, but, for now, consider this:

An object embodies a set of roles with a designated set of responsibilities.

As shown in Figure 2, an application is a community of objects working together. They collaborate by sending requests and receiving replies. Every object is held responsible. Each contributes its knowledge and services.

An object can be more intelligent if it does something with what it knows. The smarter it gets, the fewer details a client must know to use its services. So the client is liberated to do its work rather than take on the details of figuring out something that it could have been told. Blending stereotypes makes the responsibilities of clients using these hybrids easier, streamlined, and to the point. Such clients can focus on their problem, not on putting little details together that their helpers could have done. Making objects smarter has a net effect of raising the IQ of the whole neighborhood.

Making objects smarter also makes the system more efficient. Objects can stick to their specific tasks, rather than worrying about details that are peripheral to their main purpose.

When objects do collaborate, they are designed to follow certain protocols and observe specific conventions: Make requests only for advertised services. Provide appropriate information. Use services under certain conditions. Finally, accept the consequences of using them. Object contracts should describe all these terms.

However, some of the value of a given object is determined by its neighbors. As we conceive our design, we must constantly consider each object's value to its immediate neighborhood. Does it provide a useful service? Is it easy to talk to? Is it a pest because it is constantly asking for help? Are its effects the desired ones? The fewer demands an object makes, the easier it is to use. The more it can take on, the more useful it is. If an object can accommodate many different kinds of objects that might be provided as helpers, it makes fewer demands about the exact kinds of objects it needs around it to perform its responsibilities. Although we don't want an object's clients to have to know all these details, we designers must consider this as we balance what each object offers to its clients with the requirements and demands that it places on its neighbors.

Roles! Responsibilities! Collaborations! We use the roles-responsibilities-collaborations model in each of our activities to keep our focus on the behaviors of our software machinery. As our understanding of the problem grows, the roles and responsibilities of our objects evolve. We design and redesign the community's neighborhoods and the ways they interact. We reinvent the object roles and shift responsibilities among them until they "fit," work together, satisfy external constraints, and their responsibilities clearly support their purposes. We pin down more of the details until we reach the point where we can eventually bind the responsibilities to executable code.

Object Contracts

In well-bounded situations, it is possible to know a good deal about whom an object interacts with, the circumstances under which it is used, and what long-term effects an object has on its environment. These are spelled out in object contracts. They deepen our knowledge of an object's responsibilities and build our confidence in our design. Without saying how these things are accomplished, they show the conditions under which these responsibilities are called upon (conditions-of-use guarantees), and what marks they leave when they are finished (aftereffect guarantees).

An object contract describes the conditions under which it guarantees its work and the effects it leaves behind when its work is complete.

Conditions-of-Use and Aftereffect Guarantees

Knowing who collaborates with whom says nothing about when collaborations can succeed. "What do they expect from me? Under what conditions do I guarantee my services? My methods may only be called in this order!" For the designer to be confident that the object will perform the request, the requirements it places on its context must be described in its conditions-of-use. For each responsibility, any objects or internal values (or both) that affect its behavior should be noted, and any controls on them should be described.

This fine print of a contract specifies the conditions-of-use for each service and specifies the aftereffects of using each of the object's services. When an object is used outside its specified conditions-of-use, it is not obligated to fulfill the request! If an Account object has responsibilities for withdrawing cash, what are the conditions-of-use? One is that the balance be greater than or equal to the amount being withdrawn! Or it may be more complex than that, depending on the bank's policies regarding individual customers. The extra effort in describing these conditions-of-use pays off in increased reliability and robustness.

Contracts are really meaningful only in the programmer's mind. Objects don't look for advertisements and read contracts; a programmer does, and writes code with those contracts in mind.

Remember, an object's contracts with others describe how it interacts with them, the conditions under which it guarantees its work, and the effects it has on other members of the community. For our purposes in design, it is sufficient to know that particular services are clustered in interfaces and that these services will call on each other and succeed given the correct conditions.