Object Technology: Basic Concepts

OO design pioneer Rebecca Wirfs-Brock provides an introduction to basic concepts for object technology including object machinery, roles, object role stereotypes, responsibilities and collaborations, object contracts, and domain objects.

Wirfs-Brock is the lead author on the book Object Design: Roles, Responsibilities, and Collaborations and Object-Oriented Design. This is one in a series of short articles based on her work.

Object Machinery

All but the simplest of devices, both hardware and software, are designed from parts. These parts interact according to someone's plan. In a physical machine, these parts touch one another or communicate through a shared medium. Their interactions may give way to force, transfer motion, or conduct heat.

Like all good questions, "What is an object?" raises a number of others. How do objects help us think about a problem? How are object applications different? Once we have found an object solution, can we use it again for other purposes?

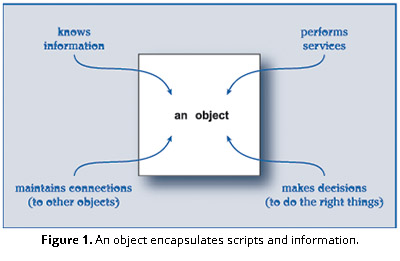

Software machinery is similar to physical machinery. A software application is constructed from parts. These parts—software objects—interact by sending messages to request information or action from others. Throughout its lifetime, each object remains responsible for responding to a fixed set of requests. To fulfill these requests, objects encapsulate scripted responses and the information that they base them on (see Figure 1). If an object is designed to remember certain facts, it can use them to respond differently to future requests.

So how do we invent these software machines?

At the heart of object-oriented software development there is a violation of real-world physics. We have a license to reinvent the world, because modeling the real world in our machinery is not our goal.

Building an object-oriented application means inventing appropriate machinery. We represent real-world information, processes, interactions, relationships, even errors, by inventing objects that don't exist in the real world. We give life and intelligence to inanimate things. We take difficult-to-comprehend real-world objects and split them into simpler, more manageable software ones. We invent new objects. Each has a specific role to play in the application. Our measure of success lies in how clearly we invent a software reality that satisfies our application's requirements—and not in how closely it resembles the real world.

For example, filling out and filing a form seems simple. But to perform that task in software, behind the simple forms, the application is validating the data against business rules, reading and refreshing the persistent data, guaranteeing the consistency of the information, and managing simultaneous access by dozens of users. Software objects display information, coordinate activities, compute, or connect to services. The bulk of this machine is our invention! We follow a real-world metaphor—forms and files—but our object model includes a much richer set of concepts that are realized as objects.

Because they have machine-like behaviors and because they can be plugged together to work in concert, objects can be used to build very complex machines. To manage this complexity, we divvy the system's behaviors into objects that play well-defined roles. If we keep our focus on the behavior, we can design the application using several complementary perspectives:

An application = a set of interacting objects

An object = an implementation of one or more roles

A role = a set of related responsibilities

A responsibility = an obligation to perform a task or know information

A collaboration = an interaction of objects or roles (or both)

A contract = an agreement outlining the terms of a collaboration

"We take a handful of sand from the endless landscape of awareness around us and call that handful of sand the world. Once we have the handful of sand, the world of which we are conscious, a process of discrimination goes to work on it. This is the knife. We divide the sand into parts. This and that. Here and there. Black and white. Now and then. The discrimination is the division of the conscious universe into parts."

—Robert Pirsig

Roles

No object exists in isolation. It is always part of a bigger machine. To fit in, an object has a specific purpose—a role it plays within a given context. Objects that play the same role can be interchanged. For example, there are several providers that can deliver letters and packages: DHL, FedEx, UPS, Post, Airborne. They all have the same purpose, if not the same way of carrying out their business. You choose from among them according to the requirements that you have for delivery. Is it one-day, book rate, valuable, heavy, flammable? You pick among the mail carriers that meet your requirements.

A role is a set of responsibilities that can be used interchangeably.

It is useful to think about an object, asking, "What role does it play?" This helps us concentrate on what it should be and what it should do. We have been speaking of objects and roles loosely. What is the real difference? When a role is always played by the same kind of object, the two are equivalent. But if more than one kind of object can fulfill the same responsibilities within the community, a role becomes a set of responsibilities that can be fulfilled in different ways. A role is a slot in the software machinery to be filled with an appropriate object as the program runs.

Object Role Stereotypes

A well-defined object supports a clearly defined role. We use purposeful oversimplifications, or role stereotypes, to help focus an object's responsibilities. Stereotypes are characterizations of the roles needed by an application. Because our goal is to build consistent and easy-to-use objects, it is advantageous to stereotype objects, ignoring specifics of their behaviors and thinking about them at a higher level. By oversimplifying and characterizing it, we can ponder the nature of an object's role more easily. We find these stereotypes to be useful:

- Information holder—knows and provides information

- Structurer—maintains relationships between objects and information about those relationships

- Service provider—performs work and, in general, offers computing services

- Coordinator—reacts to events by delegating tasks to others

- Controller—makes decisions and closely directs others' actions

- Interfacer—transforms information and requests between distinct parts of our system

Just as an actor tries to play a believable part in a play, an object takes on a character in an application by assuming responsibilities that define a meaningful role.

Software machinery is made of computation of information, maintenance of relationships, control of external programs and devices, formatting of information for display, responding to external events and inputs, error handling, and decision making.

Once we assign and characterize an object's role, its attendant responsibilities will follow. An object may fit into more than one stereotype.

But is it playing one or two roles? Often we find that a service provider holds information that it needs to provide its service. In doing so, it assumes two stereotypes—information holder and service provider—but only one role because the responsibilities are all wrapped up together for the same customers to use. If its information is being used solely to support its service, it assumes two stereotypes but only one role. But if it is perceived as serving two different types of clients for different purposes, it is likely playing two roles.

Some objects are hard to stereotype because they seem to fit into more than one category. They're fuzzy. How can you choose? You must decide what you want to emphasize. A transmission is a service provider if you emphasize the multiplication of power by the gears. It is an interfacer if you emphasize its connections to the engine and wheels. Can objects have more than one stereotype? If you want to emphasize more than one aspect, that's OK. There are blends of stereotypes, just as there are blends of emphasis.