This chapter shows the consequences of not thinking about production throughout the product creation life cycle. Without alignment, operational concerns are addressed only once production issues occur.

In Section 1.2, Alignment Using SRE, I presented an example of how a product delivery organization works without alignment on operational concerns. The example showed that without alignment, operational concerns are addressed only once production issues occur. This is done using ad hoc urgent meetings involving product operations, product development, and product management. The example is representative and can be generalized to better understand the challenge of SRE transformation.

A product delivery organization unaligned on operational concerns does not weave aspects of operations consistently and evenly throughout the product creation life cycle. Operational concerns are seen by most, as the name suggests, with production operations. Because product operations is the last part in the chain of product management, product development, and product operations, people think about operational concerns as the last thing on their to-do list. This is not a product-centric way of thinking. Users touch the product in production. Therefore, that touch point needs to be centric with all activities in the product creation life cycle. Indeed, product operations needs to be elevated and treated on par with user research, user story mapping, user experience design, architecture, and development.

The consequence of not thinking about production throughout the product creation life cycle can be illustrated using an example from the grocery industry. Imagine that a grocery store chain has a wide variety of products displayed in beautifully designed stores throughout the country, but neglects the checkout counters at the point of sale. The entire supply chain is working flawlessly, but issues arise at the checkout where the customers are trying to purchase their groceries: for example, they might not be able to pay for their groceries quickly, and the checkout queues might be getting longer. The checkout staff might not be able to resolve the issues themselves. The point-of-sale devices are supported by the operations team, which receives an enormous number of support requests. It turns out that the issues are with the software on the devices; the support team cannot resolve the software issues themselves.

While the crisis is unfolding, the developers are happily working on new features for the point- of-sale devices. The product owners are happily specifying additional new features to be handed over to the developers after they finish the current work. The operations engineers are reaching out to the developers, who are not sure whether to prioritize the requests by the operations engineers or the features in development. The developers reach out to the product owners for a prioritization decision. Finally, the operations engineers, developers, and product owners swarm over the problem and decide to fix the product issues with the highest priority.

2.1 Misalignment

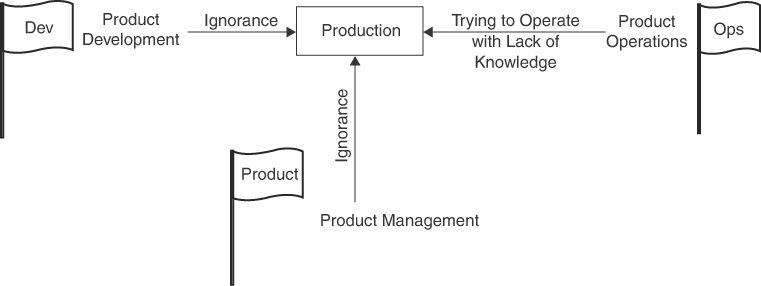

Figure 2.1 illustrates the preceding example of how a product delivery organization misaligned on operational concerns works.

Figure 2.1 Product delivery organization misaligned on operational concerns

The left-hand side of the figure shows how product development is working on the feature backlog prioritized by product management. By and large, product development ignores what is going on in production. There is no ongoing visibility into how the system is performing in production. Nor have they set up any alerts to be notified about abnormal situations. Product development’s focus is entirely on new feature development. Product operations is not part of their backlog.

Product operations is shown on the right-hand side of the figure. The product operations team is trying really hard to operate the product in production. However, they lack insider knowledge about the product in order to be able to operate it properly. This insider knowledge is with product development. Furthermore, this knowledge is changing quite rapidly with new releases being deployed to production on a frequent basis. Lacking insider knowledge about the product in operation, the operations team sets up alerts on technical resources that are visible outside. These are parameters such as memory consumption, CPU utilization, queue fill levels, disk storage fill levels, and network monitoring, among others. The parameters’ thresholds are alerted upon. Once the alerts arrive, the operations team tries to understand whether there is anything wrong with the system. Often, they have to consult the product development team to analyze potential issues. The issue backlog is growing, which frustrates the product operations team. They do not understand product development’s attitude toward solving issues in production. If production is where the customers use the product, how on earth can it be less important than anything else?

This frustration reflects a core issue in product delivery organizations that do not excel at operations. In such organizations, being product and user centric means different things to different parties. From a product operations point of view, it means production issues are tackled with the highest priority. From a product development point of view, it means features requested by product owners are developed as quickly as possible. From a product management point of view, it means user stories requested by customers are turned into features in production as quickly as possible. This fundamental misalignment of what it means to be product and user centric when approaching product creation is one of the core reasons for difficulties in operating the product in production to the customer’s satisfaction. This is where SRE contributes greatly to aligning the parties in the product delivery organization.

The product management discipline is depicted toward the bottom of Figure 2.1. Product management is very far away from production thinking. In their view, it is a job for product operations to resolve. The product management team are busy talking to executives, stakeholders, customers, partners, and users, trying to figure out where the product fits in the market, identify missed user journeys, pinpoint ways to optimize workflows, and so on. Product management maintains a backlog of features to implement. Although the backlog is prioritized, as mentioned earlier, it doesn’t consider product operations requirements. The product management team expects product development to develop and product operations to operate. This is what the names of the departments suggest, do they not?

In essence, the three parties in the product delivery organization operate under three different flags, as depicted in the figure. Product operations is proud to run under the Ops flag; they man production. Product development runs under the Dev flag; they are proud developers of new features. Product management runs under the Product flag; they are all about the product and shape it in a fundamental way: What is it? Who are the customers? What is the competition? What is the product’s competitive advantage? What are the most important user journeys? What are the features? What is on the backlog?

It turns out that in a setup like this, no one really owns production operations. Who is it, indeed? Is it product operations? Not really, because they lack the knowledge necessary to truly own production operations. There is no proper continuous knowledge transfer from product development and product management toward product operations, and vice versa.

Is it product development? Certainly not. Their focus is the feature backlog. The feature backlog is void of product operations. Shipping occasional necessary production hotfixes after escalations from product operations is not what owning production operations actually means.

Is it product management? For sure it is not. Their focus is the definition of the product. Their expectation is that product development implements the product and product operations operates it in production. Despite the word owner in their title, the product owners do not own the product all the way to and including production.

In this context, it is no wonder that it is precisely in production that the product ends up being neglected. Where there is no ownership, there is no commitment. It would require commitment from all the parties in the product delivery organization to contribute to product operations in production. But how? Who would need to commit to what to establish a meaningful partial ownership of product operations? Would the ownership of product operations be a collective ownership, then? Let us explore these questions in detail.