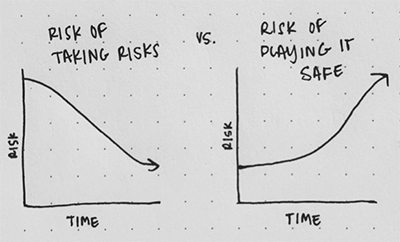

There is always risk in attempting innovation. That said, not taking any risk at all will likely be even more risky and damaging in the long run. The following simple graph makes this point very clear.

Figure P.1 There is a risk in taking a risk, but likely even a greater risk in playing it safe

As Natalie Fratto [Natalie-Fratto-Risk] suggests, it is generally the case that the risk of taking risks diminishes over time, but the risk of playing it safe increases over time. The venture investor side of Natalie can be seen in her TED Talk [Natalie-Fratto-TED], which explains the kinds of founders in whose businesses she invests. As she explains, many investors seek business founders with a high intelligence quotient (IQ), whereas others look for entrepreneurs with a high emotional quotient (EQ). She looks primarily for those with a high adaptability quotient (AQ). In fact, innovation calls for a great amount of adaptability. You'll find that message repeated in this book in several forms. Everything from experimentation to discovery to architecture, design, and implementation requires adaptability. Risk takers are unlikely to succeed unless they are very adaptable.

As we discuss our primary topic of innovation with software, it's impossible to entirely avoid the highly controversial topic of iterative and incremental development. Indeed, some form of the "A-word"—yes, agile/Agile—cannot be sidestepped. This book stays far away from promoting a specific and ceremonial way to use Agile or to be a lean business. Sadly, the authors have found that most companies and teams creating software claim to use Agile, yet don't understand how to be agile. The desire is to emphasize the latter rather than reinforce the former. The original message of agile is quite simple: It's focused on collaborative delivery. If kept simple, this approach can be highly useful. That said, this is nowhere near our primary message. We attempt only to draw attention to where "un-simple" use causes damage and how being agile helps. For our brief discussion on how we think being agile can help, see the section "Don't Blame Agile," in Chapter 1, "Business Goals and Digital Transformation."

Given our background, it might surprise some readers to learn that we do not view Strategic Monoliths and Microservices as a Domain-Driven Design (DDD) book. To be sure, we introduce and explain the domain-driven approach and why and how it is helpful—but we haven't limited our range. We also offer ideas above and beyond DDD. This is a "software is eating the world, so be smart and get on board, innovate, and make smart architectural decisions based on real purpose, before you are left behind" book. We are addressing the real needs of the kinds of companies with which we have been engaged for decades, and especially based on our observations over the past five to ten years.

We have been slightly concerned that our drumbeat might sound too loud. Still, when considering the other drums beating all around technology-driven industries, we think a different kind of drumming is in order. When many others are on high mountains, constantly beating the "next over-hyped products as silver bullets" drum, there must be at least an equalizing attempt at promoting our brains as the best tooling. Our goal is to show that thinking and rethinking is the way to innovate, and that generic product acquisition and throwing more technology at hard problems is not a strategic plan. So, think of us as the people on an adjacent mountain beating the other drum to "be scientists and engineers" by advancing beyond the ordinary and obvious, by being innovative and just plain different. And, yes, we definitely broke a sweat doing that. If our intense drumbeat leaves readers with a lasting impression that our drums made that specific brain-stimulating rhythm, then we think we've achieved our goal. That's especially so if the stimulation leads to greater success for our readers.