Training is an integral part of any enterprise software security initiative. Not surprisingly, software security training has been around for a very long time. I delivered my first "Introduction to Software Security" training course to a bunch of software architects ten years ago in 2001 just before John Viega and I published Building Secure Software. The customer was a major bank, of course. Since then, training has changed and tens of thousands of developers have experienced some kind of training. These days we have Computer-Based Training (CBT) in addition to Instructor-Led Training (ILT), and there are boatloads of courses to choose between.

So why write about software security training? Because many things have changed over the years when it comes to software security training, and we have more data than ever to draw from.

Old Lessons Still Apply

Back in February 2006 when the Software [In]security column was being published by IT Architect magazine, I wrote an article that posed the question "Is Application Security Training Worth the Money?". The answer back then was:

If the course you choose is 1) taught by software people, 2) focuses on design flaws as well as bugs, and 3) covers software security touchpoints, you'll find it worth the money. Otherwise you might as well spend it on beer.

Five years later, all of those early lessons still apply: 1) developers and other software professionals only pay attention to instructors with software chops, so make sure that your trainers are actually software people (and not just good network security people); 2) though security features such as cryptography and authentication systems are interesting fodder for courseware, make sure that you focus most of your training attention on uncovering and eradicating security defects in your entire software base; and 3) ensure that your training curriculum covers best practices from every phase in the Security Development Lifecycle (SDLC) from design through coding to testing to fielding. Don't over focus on implementation level bugs like the OWASP top ten, and don't forget to include content for executives, product managers, and testing people in your curriculum.

What the BSIMM Data Have to Say About Training

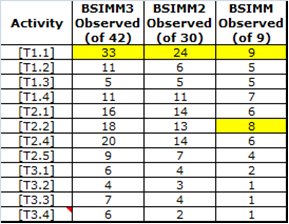

Training plays a central role in the BSIMM. It is one of the twleve key practices in the Software Security Framework and includes twelve particular activities divided into three levels. Here's what the BSIMM document (now in its third major revision) has to say about training:

The overall goals for the Training practice are the creation of a knowledgeable workforce and correcting errors in processes. The workforce must have role-based knowledge that specifically includes the skills required to adequately perform their SSDL activities. Training must include specific information on root causes of errors discovered in process activities and outputs.

Here are the activity data for the Training practice for all three versions of the BSIMM study. For what it's worth, these data have a unique characteristic in the BSIMM since the levels of activities do not directly break into neat bands. Usually, level one activities (easy) are very commonly observed and the bands between levels are quite obvious. That is, level two stuff (harder than level one) is less common than level one, but more common than level three (rocket science). Only in the training practice are three of four level two activities more commonly observed than three of the four level one activities. (There is enough discrepancy here that we may need to adjust the Training practice for BSIMM4.)

Here is one way to understand what is going on with these data. T1.1 Provide awareness training, T2.1 Offer role-specific advanced curriculum (tools, technology stacks, bug parade), and T2.4 Offer on-demand individual training all involve things you can buy and roll out. We've seen great growth in all three of these easy-to-buy activities. T2.2 Create/use material specific to company history is a more of a cultural thing, and we've seen the culture change toward this kind of openness in the Technology and Independent Software Vendor verticals, but not in the Financial Services vertical (where security issues are still in some sense "classified"). On the other side of the coin, T1.2 Include security resources in onboarding, T1.3 Establish SSG office hours, and T1.4 Identify satellite through training take real SSG person-hours and process inside of a given firm. The implication here is that companies in the BSIMM study are adopting activities they can buy before adopting activities they have to create and staff.

This is an interesting enough trend that we plan to look into whether it applies to activities in the other eleven practices as well.

We have put off adjusting the Training practice in the model twice (between each major BSIMM release). If the data trends continue into BSIMM4, we will likely need to demote three level 2 activities to level 1 activities and promote three level 1 activities into level 2 activities. That is a fair amount of change, but the data are beginning to demand it.

What We Have Learned Through Consulting

Cigital has been offering software security training since 2001. We estimate that we have trained over 14,000 people since that time with ILT. Around 2006, the market demanded (and continues to demand) standardized "Introduction to Software Security" training for all SDLC stakeholders and more advanced training for architects and developers (usually focused around technology stacks).

Cigital's CBT courses have been deployed to 105,000 or so students (developers, architects, testers, managers, business analysts, security operations folks, and others) since 2007. A majority of clients are hosting our eLearning content in their own internal learning management systems for access by employees and contractors. As you can see, the CBT headcount number outstrips the ILT number by a factor of 7.5.

We've seen some significant changes in the Training part of the software security market. First, most firms have come to realize they are not a special snowflake when it comes to writing secure code. For years, the vast majority of firms felt that software security training had to be an exact, customized match for their skill levels, their technology stacks, their SDLC, their coding standards, and even their IDEs. It took a while for many firms to understand that the origin of their XSS and CSRF bugs, for example, was probably not their choice of IDE or SDLC, it was rather tied up in how their code was being attacked based on its design and implementation.

Second, eLearning or CBT has become a necessity for large firms. There simply isn't enough time (nor are there enough dollars) to roll out classroom instruction for everyone. While eLearning should not be any firm's sole skill building endeavor, it is a valuable tool for aiming large groups in the same direction.

Third, there is a distinct trend towards shorter training modules that focus on specific problems and solutions. Even just a year or two ago, everyone wanted comprehensive modules that walked the student through a full story. Now that software security has seeped into the public consciousness, it appears that most students just want the answer, not the story of why it's the answer. (This is probably not a good thing, but it is a trend nonetheless.)

If You Build It, You Still Have to Make Them Come

Zooming further out from the data, one of the most common problems we are seeing in our own training delivery work is the problem of extremely busy developers not taking advantage of the training courses on offer. This is especially true when it comes to CBT and eLearning. The training is there, but nobody is taking it.

There are several techniques you can use to address this problem. One tactic is to make training mandatory and tie successful completion to raises and promotions (draconian and effective, but not always appropriate in all company cultures). A second tactic is to make sure that the training is directly relevant to the work a developer is being asked to do (right now). This one is so important that we'll come back to it below under the guise of real-time training. A third tactic is to provide incentives and rewards for completion of training. Sometimes this can be in the form of career progression or other "gold stars."

In any case, all students must be given the time to take and absorb software security training. Trying to squeeze training into an already packed sprint isn't going to accomplish anything useful.

Real-Time Training

For all the analyst chatter about SAST versus DAST, hybrid analysis, and so on, software security does nobody any good unless the code gets fixed. That's why training is so important. We don't want to put all of our dollars into a "code as you see fit, we'll find the bugs later" hamster wheel of pain. We want to avoid creating bugs in the first place! (And in any case, we certainly want to fix those bugs that we do find.)

One idea is to squash newborn bugs before they are even commited to a code base. This means getting between the keyboard and the code pile. Real-time training can do this. That's because training teaches a developer to prevent bugs from entering the code base rather than focusing on finding bugs using tools later in the process.

The simple idea is to integrate rudimentary scanning capability into the IDE itself so that as a developer is typing in a potential vulnerability, we immediately put a stop to it and show her a better way to proceed. (Ironically, this is one of the ideas proposed way back in 2000 with the introduction of the world's first code scanner, ITS4: http://www.cigital.com/papers/download/its4.pdf.) We have been experimenting with this approach at Cigital through a tool called SecureAssist and the results are very encouraging. We are busy integrating the resulting toolset into our standard secure SDLC.

As a developer using SecureAssist works on code where risk could be introduced, guidance is automatically "pushed" to the developer, providing just-in-time information to reinforce training. Just as a document spellchecker detects spelling and grammar issues, SecureAssist detects when risky code is created that could ultimately result in a security bug.

Software Security Training is Not Just for Us Geeks

Don't forget that software security training is not just for developers. Every stakeholder in your SDLC requires some software security training. This includes business analysts (who, with help, should consume threat models and misuse/abuse cases to make non-functional security requirements), architects, testers, development managers, software risk managers, and everyone who is tasked with either defining some part of a software security initiative or executing it.

In the most successful programs we've seen, training is an integral part of the software security initiative strategy. That is, it doesn't simply exist; it reinforces and promotes the local software security process while also imparting important skills. This requires a thoughtful, role-based approach that arms all secure SDLC stakeholders to get their job done.