Good Ideas That Never Die

I have been talking about, writing about, and doing software security for well over a decade. Sometimes I feel like I am endlessly repeating myself, but every time I start to fret, it seems that hundreds of new people have joined the field and are clammoring to learn the basics. Maybe this should not come as a surprise. As it turns out, software security is still a relatively new field and it is growing like a weed. While software security continues to scale as a discipline, we can expect a massive influx of newbies.

So though software security may seem obvious to many of my loyal readers, it is still just catching on out there—especially in the middle market. Reviewing basic concepts makes perfect sense.

Just to make this fun, I have started referring to basic concepts as "zombies" since (hopefully) they will never die.

Here is a short list of software security zombies:

- Network security alone will not solve the computer security problem

- Security software is not software security

- The more code you have, the more security bugs you will have

- Software security practices should be integrated into the software development lifecycle (SDLC)

- Software security defects come in two main flavors—bugs at the implementation level (code) and flaws at the architectural level (design)

- Badness-ometers are not security meters

Zombie(s): Network Security FAIL

When I was getting started in computer security in 1995, the idea of defending the perimeter of a local area network with a firewall was just beginning to take off. We built our first firewall at Cigital using Marcus Ranum's fwtk toolkit running on a stripped down Linux box. Now everybody and their dog has a firewall and there are many popular commercial firewall products generating billions in annual revenue. Unfortunately, firewalls did not solve the computer security problem. In fact, by most measures the computer security problem is bigger than ever.

The idea behind network firewalls is simple: protect the valuable stuff from the bad people by putting a barrier between the bad people and the stuff. The problem is that for the most part firewalls and perimeter security have failed. That's because the valuable stuff is more often than not a set of Internet-exposed applications and associated data that are completely broken from a security perspective. Modern attackers bypass the firewall and go straight for the broken apps.

The root of the problem is that perimeters are hard to come by in the age of massively distributed applications, mobile devices, and cloud services. If that were not the case, maybe we could protect some of the more simplistic broken apps with a firewall or two. However, the nature of the Internet and in particular computation on the Internet has evolved so much that simply protecting machines from network traffic—and assuming that you can spot the "bad" packets—is not tenable as a solution (cloud security anyone?). Sure, we need to keep our network firewalls up and running, but we also need to build more secure software if we want to begin to solve the computer security problem. In other words we need to make sure that the valuable apps stuff is not broken.

The idea of fixing broken software after it has been copmpromised (a.k.a. penetrate and patch) may look better than a firewall on paper (especially if software applications are subjected to penetration testing), but such approaches happen so late in the software lifecycle that they are often economically infeasible. If you perform a security review on a product when it is complete, don't be surprised when it turns out to be a security disaster that is prohibitively expensive to clean up. Like quality, security is something that is built in to a system, not bolted on. And the earlier in the lifecycle you start working on security, the more cost effective your approach will be.

This vexation of network security zombies is as old as the hills, but there are still some security types who don't get it. If you want to protect your software from being compromised, you have to build solid software that can withstand attack.

Zombie: Security Software is not Software Security

There are plenty of vendors who would like to sell you some software mechanisms to solve the software security problem. They're missing the point. This notion of bolting security on (or sprinkling it on like so much magic crypto fairy dust) is all too common among developers. Know why? Developers think in terms of functions and features. That's why eight out of ten developers today will (still) tell you their application is secure because they "use SSL." They think security is a thing. Security is not a thing, it is a system-wide property. Getting software security right is just as much about building code that does not fail when it is under attack as it is about security features.

Zombie: More Code, More Bugs

The good news is that we are getting much better at building secure software. Projects like the BSIMM teach us how software security happens at the enterprise level and provide a way to measure progress. Static analysis tools help uncover security bugs in code so they can be eradicated before release. In general, our experience shows that defect density rates (that is number of defects per KLOC) are dropping among those development shops practicing software security.

The bad news is that we're building even more code even faster than ever. So though the number of bugs "per square inch" is dropping, the number of "square miles" of code is growing faster than ever. Put pithily: the more code we produce, the more security bugs we will have.

One alternative to developing new code and creating more security issues is deleting old code. I used to say this as a tongue in cheek joke, but I have come across more than one dev shop that understands that the best way to remove bugs is to delete code. Legacy code is often one of the biggest software security nightmares, so if you can retire software, by all means do so. At the same time, make sure that any new software you buy or build has software security built in as an emergent property of the system.

Zombie: SDLC integration

When I wrote Building Secure Software with John Viega back in 2001, there were very few software security practices to draw on. We all knew we needed to build better software, but we had only vague ideas about how. Ten years later everyone agrees that integrating software security practices into your SDLC (or more realistically your SDLCs) is the way to go.

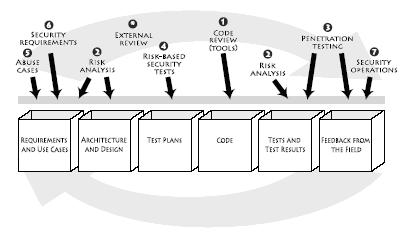

My 2006 book Software Security describes a number of software security best practices that I call the Touchpoints (see Figure 1). Those best practices can be adopted regardless of your SDLC since they are process agnostic. Microsoft has a very similar approach to SDLC integration called the SDL (though it is specific to Microsoft's corporate SDLC).

Figure 1: The Touchpoints as described in the book Software Security is a process-agnostic methodology for software security espousing a seven best practices associated with standard software artifacts.

The BSIMM reveals that a great majority of organizations tackling software security do so in a principled way, most often following a home-grown methodology that mixes parts of the Touchpoints and the SDL. These days no serious software security practitioner believes that any particular point solution (e.g., a code review tool or an application firewall) will solve the problem on its own. If your organization is serious about software security, you should join the BSIMM Project and learn from the best.

Zombie: Bugs and Flaws are 50%/50%

To hear the tools vendors tell it, we could immediately solve the software security problem on planet earth if we just ran all of our code through a magic source code scanning tool. Sadly, there are a couple of things wrong with this picture. The first is that source code scanning tools are great at finding problems, but they don't fix them. Fixing security bugs is the real battle, with mitigation efforts finally beginning to take precedence over bug finding efforts.

The second problem with bug finding tools is that they only find bugs. No scanning tool can find architectural flaws, and flaws account for 50% of the software security defect count. (To read more about software security flaws, pick up a copy of Software Security.)

To find flaws, you need to adopt an approach to Architectural Risk Analysis (ARA) that is fully informed by Threat Modelling. Unfortunately, ARA is hard and requires real expertise and experience. The best bet may be to hire some experienced help.

Zombie: Badness-ometers are Useful, but not as Security Meters

Many automated security tools (especially black box style tools) provide limited security assurance by running tests against a system dynamically. The reasoning goes, if a set of canned tests finds security problems in your system, then you need to take another crack at software security. Such testing tools are cheap and are well worth using.

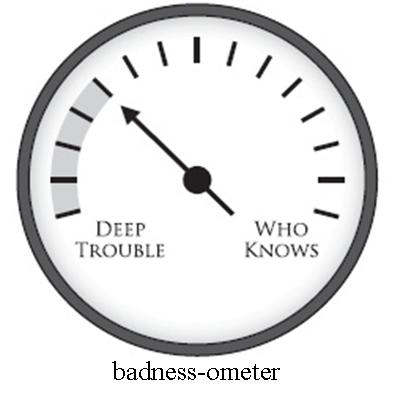

However in your rush to use this automation, don't forget that tools of this type are badness-ometers and not security meters. Understanding this is fairly straightforward. If a canned test finds problems in your software, you know your software is in a world of hurt. However, if none of the canned tests break your software, that does not mean that your software is secure, it means only that some small number of tests have been run and nothing of interest was found. Hence the term "badness-ometer" (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: A badness-ometer can tell you if you are in deep trouble, but it can't tell you if you are secure.

Many many processes in software security amount to badness-ometers, and it is essential that we remember what we're doing and what we're measuring from a security perspective. If a vendor or a group of vendors or worse yet the Department of Homeland Security tells you that they have a way of measuring security in software automatically, they are making stuff up. I wish we could measure software directly for security, but technical impossibility is hard to argue against (Halting Problem anyone?). Just because a piece of software does not contain ten certain bugs does not make it secure.

Zombie Baby: Fix the (Dang) Software

To wrap things up here is a freshly-hatched "baby zombie." Hopefully it will grow up to live forever too.

The narrative in software security these days is all about finding bugs. Big rowdy arguments break out over which technique is best for finding security bugs (static versus dynamic, black box versus white box, source code based versus system based). Analysts spill plenty of ink writing about SAST, DAST, and hybrid methods. The problem is, finding bugs is not what the problem is. Fixing bugs is what the problem is.

The time has come to focus on fixing security problems in software as opposed to simply finding them and collecting them up in a giganic cesspool to be indefinitely ignored. The questions to be asked should be: Which of these bugs should I fix first? If I only have limited resources, how should I allocate them? How do I best improve my actual security posture from a software perspective?

Hopefully these undead software security zombies can be corralled into marauding in your organization in the name of better software security!