Design Patterns 15 Years Later: An Interview with Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, and Ralph Johnson

Larry O'Brien: 85,000 apps for the iPhone have been developed and deployed in the past year-and-change. One can write a globally-accessible "Hello, World! The time is X" Web page in just one line of PHP, for instance. "Designing object-oriented software is hard," are the first words of Design Patterns. Are those words still accurate?

Richard Helm: Software design is always hard. Although most modern development environments do lots to reduce complexity through reusable libraries and toolkits (Eclipse, Apple, Microsoft), designing a software solution to the business problem is still hard.

Erich Gamma: Yes, and it is funny that you mention the iPhone. The iPhone SDK is based on the NeXTStep object-oriented frameworks like the AppKit. It already existed when we wrote Design Patterns 15 years ago and was one source of inspiration. We actually refer to this framework in several of our patterns: Adapter, Bridge, Proxy, and Chain of Responsibility.

Richard: Which is a great example of the enduring nature of good design, and how it survives different technical manifestations.

Ralph Johnson: Writing one-line programs is not usually what we mean by design. Software has improved a lot over the years, and a lot of systems that used to require careful design can now be built by reusing other software. But there are a lot of systems that we can't build that way, and writing 100K lines of new code isn't that much easier now than it was 15 years ago. It will do a lot more, but costs the same.

Designing software is hard. That is what makes it so fun! People who are good at designing software enjoy solving hard problems, at bringing order to chaos, at overcoming difficulties. Things that used to be hard are now easy, but we have moved on to working on problems that would have been impossible 20 years ago. OO programming helps but does not eliminate the difficulty of design.

Larry: The next phrase in the book is "...designing reusable object-oriented software is even harder." Reuse was, in the early 90s, presented as object-orientation's main benefit. But in the past decade, it seems that many mainstream developers have decided to leave reuse to the framework designers. Develop what you need today, do the minimal refactoring if you need to evolve it, and, if questioned, play the "You Ain't Gonna Need It," card. Is striving for reusable design an important goal for today's developers?

Richard: I think there has been an evolution in level of sophistication. Reusable software has migrated to the underlying system/language as toolkits or frameworks—and mostly should be left to the experts.

The goal for most software developers still remains to design for change—and there the debate is do you do it early (given foreknowledge) or later (once more is known and you know you need it)? In many cases the design should be refactored, and the patterns provide a target to do this.

Erich: Actually, I'd now add an additional phrase "... the hardest is evolving reusable object-oriented software." We touch on this a little bit in Design Patterns. For example, factories, adapters and facades can help when it comes to changing and evolving a reusable library. There are some additional patterns for this problem that would be worthwhile capturing.

I agree that designing durable APIs requires an additional level of sophistication. Decisions you make today will impact what you can do tomorrow. However, even experts have a hard time to get it right the first time. For example, if you dive into the Eclipse APIs you will find three different versions of the API to store preferences.

Ralph: Most programmers are not hired to write reusable software, except in the sense that the software needs to be usable years later, when requirements change and the world is a different place. On the other hand, they need to know how reusable software works, and our patterns are common in reusable software, so they are still useful for the average programmer to know. Perhaps it would be better now to aim the book at people using patterns chosen by others rather than aim it at people trying to figure out which pattern to use.

Erich: I like this idea. When I learned the iPhone SDK as I mentioned above, I noticed that I felt quickly familiar with the library, since I knew the used patterns.

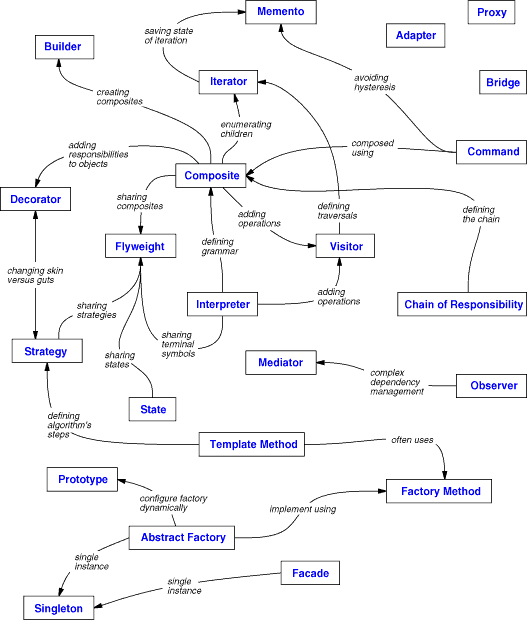

Larry: For a while, everything became a "pattern." There were patterns for architecture, organizational behavior, analysis, etc. What was less apparent, though, was an evolution where the 23 patterns in the DP catalog were extended by X other design patterns or related to, say, architectural patterns. There are a lot of patterns out there. Is there a new "Figure 1.1: Design pattern relationships"?

Ralph: If you mean "Do we have a figure to give you?" the answer is "No." If you mean "Should someone create a new figure?" the answer is "Yes."

Erich: There is the Patterns Almanac 2000 from Linda Rising that attempted to capture many patterns. It was a significant amount of work, but didn't get as much traction in the community. I start to think that social filtering would help to find out the most popular patterns and get hints like "people that found this pattern useful have also liked this one...". In other words, not all patterns have the same relevance and weight. We were pretty lucky that we picked a good sample of patterns in DP.

Larry: The description template used in DP had a lot of features beyond Name, Intent, and Structure. Not everyone who jumped on the patterns bandwagon provided all those elements. If you were to refactor that template today, what would you do to it?

Ralph: The template was okay for low-level object-oriented patterns like the ones in our book. It was not good for other purposes. People quickly found that out and chose different templates. Every collection of patterns needs a standard template, but I don't think any template will ever be good for all patterns. So, I find arguments about templates boring.

Erich: I'm not attached to a particular template. I'm glad that we eventually agreed on one and then stuck to it. It helped us to achieve consistency and forced a level of completeness, e.g., do we have known uses, do we describe the consequences.

Larry: After the pattern bandwagon, there was a trend towards "anti-patterns." Are anti-patterns as valuable as patterns?

Richard: Probably—they provide a way to share and learn from mistakes

Ralph: I prefer the notion of "code smells," or "design smells"/"architecture smells" etc. They aren't always mistakes. Sometimes they are just problems you have to live with. For example, "stove pipe" systems grew up partly because companies didn't have good ways of interconnecting their systems, partly because technology was changing rapidly, and partly because the different parts of a company didn't cooperate. In a mature, slowly growing company, stove pipe systems are an architecture smell that should probably be eliminated using SOA and a strong architecture team. But in a company that is growing rapidly by buying other companies, stove pipes are due to the fact that it takes time to integrate a new company. No amount of architectural leadership will eliminate the problem.

Some of my students wrote a pattern for "Big Ball of Mud." For most people who read patterns, this is an anti-pattern to be avoided at all costs. But to a lot of IT organizations, especially ones I've seen in government, there just isn't enough expertise to do better. Anything they build will, in a few years, lose its structure and become connected with everything else.

Erich: Using a code smell or anti-pattern to motivate the use of a design pattern is valuable. It is difficult to appreciate the value of a design pattern without seeing the code before and after the use of a design pattern.

Larry: GoF came out relatively early in the ascent of OOP as the mainstream paradigm and, for better or worse, "patterns" seem to be associated with OO approaches. You even hear functional and dynamic advocates boasting that their languages "don't need" patterns. How do you respond to that?

Erich: Just as an aside, it is also easy to forget that we wrote design patterns before there was Java or C#.

Ralph: Some of those languages don't need some of the patterns in Design Patterns because their languages provide alternative ways of solving the problems. Our patterns are for languages between C++ and Smalltalk, which includes just about everything called "object-oriented," but they certainly are not for every programming language. I don't think anybody actually says that programmers in other languages don't need patterns; they just have a different set of patterns.

Erich: Design patterns eventually emerge for any language. Design déjà-vu is language neutral. While these experiences are not always captured as patterns, they do exist. The design principles for Erlang come to mind.

Larry: Where would a person go to learn about patterns for dynamic and functional languages? Who's making good contributions?

Ralph: If by "dynamic" you mean dynamic object-oriented languages like Smalltalk, Ruby or Python, then our patterns are applicable. Functional languages require different patterns, but I don't know who is working on them.

Larry: OOP provides a combination of static and dynamic structure, allowing the design intent to be communicated along a few different axes (or at least with different diagrams). With today's emphasis on functional and meta-programming approaches, there's not as much static structure. Instead, there's a lot of talk about communicating design intent by creating APIs in the context of a "domain-specific language" or a "fluid interface." Do these approaches replace or complement the patterns in DP?

Richard: Complement. Rich class libraries structured well using good design take on features/characteristics of domain-specific languages. Reading code for a well designed user-interface toolkit becomes like reading a domain-specific language for GUIs. The library constructs become the verbs and nouns of the domain-specific language. For example, if you go back and look at the code in Interviews/Unidraw (co-written by John Vlissides), although the language was C++, the code could easily be understood by someone who knew how to build GUIs.

Erich: While they complement the patterns in DP it can indeed be the case that meta-programming can replace the design pattern used in a design. The evolution of JUnit 3 to JUnit 4 comes to mind. JUnit 3 was a small framework that used several patterns like Composite, Template Method and Command. JUnit 4 leverages the Annotations meta-programming facilities introduced in J2SE 5.0. The use of the patterns disappeared and the framework evolved into a small set of annotations plus a test runner infrastructure that executes the annotated Java code.

Larry: Generative patterns: There are 253 patterns in A Pattern Language and 23 in DP. Do you think the DP catalog fulfills Alexander's edict that "[A pattern language] not only tells us the rules of arrangement, but shows us how to construct arrangements—as many as we want—which satisfy the rules"?

Richard: No. It was not the intent to be a prescriptive or generative guide. The inspiration for me came more from engineering handbooks where an engineer/designer would reach up to his bookshelf and find a generic mechanical design for clutches or two stroke engines.

Larry: How would you refactor "Design Patterns"?

Erich: We did this exercise in 2005. Here are some notes from our session. We have found that the object-oriented design principles and most of the patterns haven't changed since then. We wanted to change the categorization, add some new members and also drop some of the patterns. Most of the discussion was about changing the categorization and in particular which patterns to drop.

When discussing which patterns to drop, we found that we still love them all. (Not really—I'm in favor of dropping Singleton. Its use is almost always a design smell.)

So here are some of the changes:

- Interpreter and Flyweight should be moved into a separate category that we referred to as "Other/Compound" since they really are different beasts than the other patterns. Factory Method would be generalized to Factory.

- The categories are: Core, Creational, Peripheral and Other. The intent here is to emphasize the important patterns and to separate them from the less frequently used ones.

- The new members are: Null Object, Type Object, Dependency Injection, and Extension Object/Interface (see "Extension Object" in Pattern Languages of Program Design 3, Addison- Wesley, 1997).

- These were the categories:

- Core: Composite, Strategy, State, Command, Iterator, Proxy, Template Method, Facade

- Creational: Factory, Prototype, Builder, Dependency Injection

- Peripheral: Abstract Factory, Visitor, Decorator, Mediator, Type Object, Null Object, Extension Object

- Other: Flyweight, Interpreter

As I said above these are just notes in a draft state. Doing a refactoring without test cases is always dangerous...